Long before Apollo astronauts set foot upon the Moon, much remained unknown about the lunar surface. While most scientists believed the Moon had a solid surface that would support astronauts and their landing craft, some believed a deep layer of dust covered it that would swallow any visitors. Until 1964, no closeup photographs of the lunar surface existed, only those obtained by Earth-based telescopes and grainy low-resolution images of the Moon’s far side obtained in 1959 by the Soviet Luna 3 robotic spacecraft. On July 28, 1964, Ranger 7 launched toward the Moon, and three days later returned not only the first images of the Moon taken by an American spacecraft but also the first high resolution close-up photographs of the lunar surface. The mission marked a turning point in America’s lunar exploration program, taking the country one step closer to a human Moon landing.

Left: Block I Ranger 1 spacecraft under assembly at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California. Middle: Block II Ranger spacecraft, showing the black-and-white spherical landing capsule. Right: Block III Ranger 7 spacecraft under assembly at JPL.

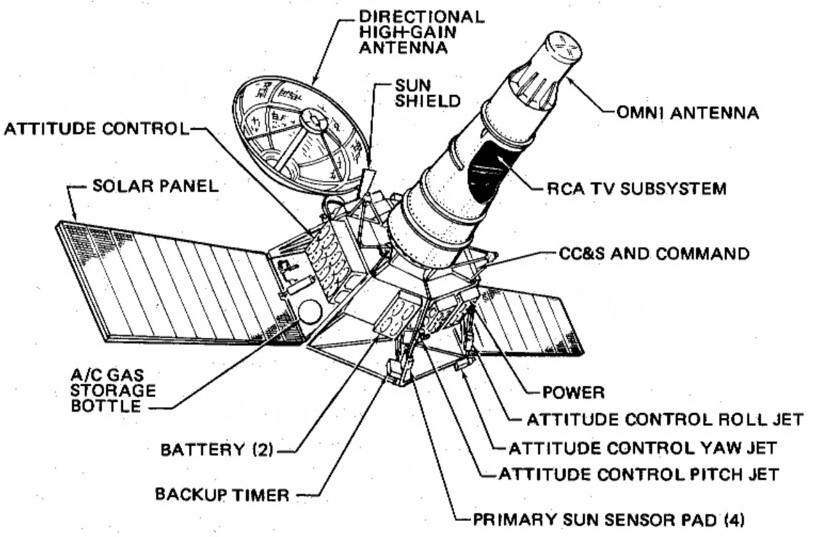

The Ranger program, initiated in 1960 and managed by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, sought to acquire the first high resolution close-up images of the lunar surface. The program consisted of three phases of increasing complexity. The first phase of the program, designated “Block I,” intended to test the Atlas-Agena launch vehicle by placing a Ranger spacecraft in a highly elliptical Earth orbit where its equipment could be tested. The second “Block II” phase built on the lessons of Block I to send three spacecraft to the Moon to collect images and data and transmit them back to Earth. Each Block II Ranger carried a television camera for collecting images, a gamma-ray spectrometer for studying the minerals in the lunar rocks and soil, and a radar altimeter for studying lunar topography. These spacecraft carried a capsule, encased in balsa wood to protect it from the impact of landing, containing a seismometer and transmitter that would be able to operate for up to 30 days after being dropped on the lunar surface. The final “Block III” phase consisted of four spacecraft that each carried a high-resolution imaging system consisting of six television cameras with wide- and narrow-angle capabilities. They could take 300 pictures per minute.

The Block I and II Rangers met with limited success. Neither Ranger 1 nor 2 left low Earth orbit due to booster problems. Ranger 3, the first Block II spacecraft, missed the Moon by 22,000 miles and sailed on into solar orbit, returning no photographs but taking the first measurements of the interplanetary gamma ray flux. Ranger 4 has the distinction as the first American spacecraft to impact the Moon, and on its far side to boot, but due to a power failure in its central computer could not return any images or data. Ranger 5 missed the Moon by 450 miles but also failed to return images due to a power failure and entered solar orbit. None of the Block II Rangers delivered their seismometer-carrying capsules to the Moon’s surface. Ranger 6, the first Block III spacecraft, successfully impacted on the Moon in January 1964, but its television system failed to return any images due to a short circuit. NASA and JPL delayed the next mission until a thorough investigation identified the source of the problem and engineers completed corrective actions. All hopes rested on Ranger 7 to redeem the program.

Left: Schematic diagram of a Block III Ranger, showing its major components. Middle: The television camera system aboard Ranger 7. Right: Launch of Ranger 7.

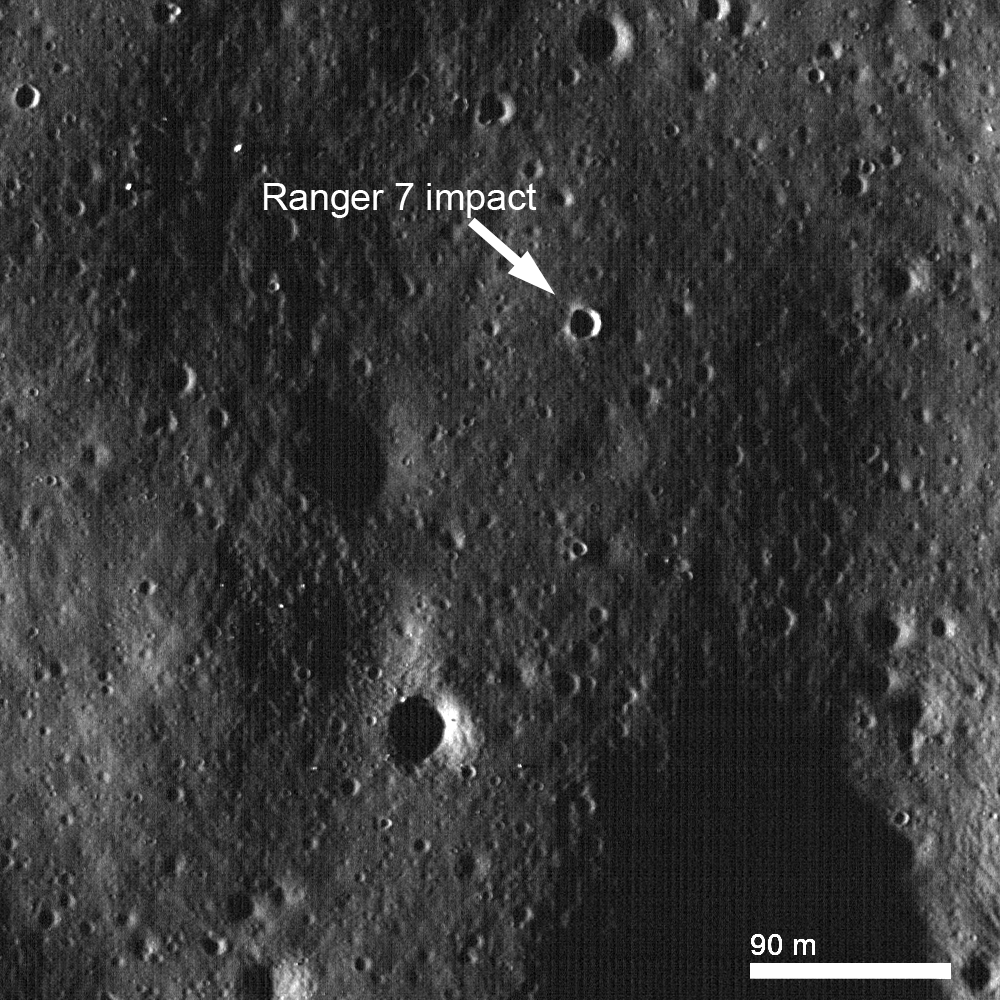

On July 28, 1964, Ranger 7 launched from Cape Canaveral, Florida. The Atlas-Agena rocket first placed the spacecraft into Earth orbit before sending it on a lunar trajectory. The next day, the spacecraft successfully carried out a mid-course correction, and on July 31, Ranger 7 reached the Moon. This time, the spacecraft’s cameras turned on as planned. During its final 17 minutes of flight, the spacecraft sent back 4,308 images of the lunar surface. The last image, taken 2.3 seconds before Ranger 7 impacted at 1.62 miles per second, had a resolution of just 15 inches. Scientists renamed the area where it crashed – between Mare Nubium and Oceanus Procellarum – as Mare Cognitum, Latin for “The Known Sea,” to commemorate the first spot on the Moon seen close-up.

Left: Ranger 7’s first image from an altitude of 1,311 miles – the large crater at center right is the 67-mile-wide Alphonsus. Middle: Ranger 7 image from an altitude of 352 miles. Right: Ranger 7’s final image, taken at an altitude of 1,600 feet.

Left: Impact sites of Rangers 7, 8, and 9. Middle: The Ranger 7 impact crater photographed during the Apollo 16 mission in 1972. Right: Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter image of the Ranger 7 impact crater, taken in 2010 at a low sun angle.

Two more Ranger missions followed. Ranger 8 returned more than 7,000 images of the Moon. NASA and JPL broadcast Ranger 9’s images of the Alphonsus crater and the surrounding area “live” as the spacecraft approached its crash site in the crater – letting millions of Americans see the Moon up-close as it happened. Based on the photographs returned by the last three Rangers, scientists felt confident to move on to the next phase of robotic lunar exploration, the Surveyor series of soft landers. The Ranger photographs provided confidence that the lunar surface could support a soft-landing. Just under five years after Ranger 7 returned its historic images, Apollo 11 landed the first humans on the Moon.

Enjoy a brief video about Ranger 7, or a more detailed video of the entire mission.

9 min read 25 Years Ago: STS-93, Launch of the Chandra X-Ray Observatory Article 5 days ago

9 min read 25 Years Ago: STS-93, Launch of the Chandra X-Ray Observatory Article 5 days ago  11 min read 45 Years Ago: Space Shuttle Enterprise Completes Launch Pad Checkout Article 5 days ago

11 min read 45 Years Ago: Space Shuttle Enterprise Completes Launch Pad Checkout Article 5 days ago  5 min read Eileen Collins Broke Barriers as America’s First Female Space Shuttle Commander Article 1 week ago

5 min read Eileen Collins Broke Barriers as America’s First Female Space Shuttle Commander Article 1 week ago